"Surprisingly, though, evil is actually evidence for God, not against Him." — Greg Koukl

"True evil is evidence for God’s existence." — J. Warner Wallace

"But because there is evil and because theism better predicts or explains those things needed to make sense of evil, then evil provides great evidence for the existence of God." — Pat Flynn

"While the existence of evil is a serious problem, it is an even more serious problem for atheists because the existence of evil is only further evidence for God’s existence." — Daniel King

"Again, the problem of evil—the leading anti-theistic argument—turns out to be an argument for God’s existence." — Paul Copan

Introduction

The problem of evil comes in two varieties: the logical version and the evidential version. In the logical version of the problem, the existence of evil is supposed to be logically inconsistent with theism, where theism is the thesis that there exists an omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good creator of the universe (God). This version of the problem has been almost completely abandoned by contemporary philosophers of religion (James P. Sterba is a noteworthy exception—see his book Is a Good God Logically Possible?). In the evidential version of the problem, the existence of evil is supposed to provide (strong) evidence that theism is false, where evidence is generally cashed out in probabilistic terms.

In either version of the problem, the atheist is on the offensive, and the theist is on the defensive. The two most prevalent defensive strategies in response to the problem of evil are theodicies and skeptical theism. The former consists in offering justifying reasons for why God would allow the evil that we see in the world. The latter consists in arguing that we are—due to our cognitive limitations as epistemically finite creatures—not in any kind of position to accurately assess the evidential impact that evil has on theism.

In this post, I want to consider an alternative defensive strategy that is fairly prevalent in popular level apologetics. In a nutshell, the strategy is to turn the problem of evil on its head by arguing that not only is evil not evidence against God, but it is actually evidence for God. The basic idea is that if true, objective evil exists, moral realism must be true, i.e., there must be such a thing as objective moral values and/or duties. Therefore, insofar as the problem of evil presupposes the existence of objective evil, it follows that it must also presuppose moral realism. As Greg Koukl puts it, "The argument against God based on the problem of evil can only be raised if some form of moral objectivism is true" ("Evil as Evidence for God").

From here, the strategy is to argue that God provides the best explanation of the truth of moral realism in such a way that either moral realism entails that God exists or, at the very least, moral realism is (strong) evidence that God exists. This is, in a nutshell, the moral argument for the existence of God. The idea, then, is that the problem of evil can be turned against the atheist by successfully defending the moral argument for God. I will call this strategy reversing the problem of evil.

At face value, assuming that the moral argument for God can be successfully defended, this might seem like a compelling strategy to adopt in response to the problem of evil. Indeed, several authors on the popular apologetics scene present this strategy as if it were a coup de grace against the problem of evil. However, as will be seen, when we attend to the details of the argumentation, it turns out that it is far from obvious that this strategy is viable. For the arguments on offer are either fallacious or inadequately defended.

My plan of attack for the remainder of this post is to survey several popular apologetics articles that argue for the claim that evil is evidence for God's existence. I will show that the arguments can be boiled down to two similar but distinct arguments. I will then show that the first argument does not in fact establish the claim that evil is evidence for God's existence, even if all of its premises are granted. Further, I argue that the second argument is only guaranteed to establish such a claim if its premises can be known with complete certainty, which is an unrealistic assumption. Apart from this assumption, the argument as it is presented is inadequately defended. Finally, I offer an alternative argument which, if sound, would establish the claim that evil is evidence for the existence of God. Rather than defend this argument myself, I merely offer it for consideration and suggest that advocates of the strategy of reversing the problem of evil would do well to explore it further.

Background: Evidence and Probability

Before getting to the articles, however, since much of the discussion will be centered around the concept of evidence, it is important to know just what we are talking about when we speak of evidence. As such, I begin with the following standard Bayesian account of evidence:

Bayesian Evidence: Let H be a hypothesis and E be a piece of evidence. Then,

- E is evidence for H means that Pr(H | E) > Pr(H).

- E is evidence against H means that Pr(H | E) < Pr(H).

(1) says that what it means to say that E is evidence for H is that the conditional probability of H given E is greater than the prior probability of H (i.e., the probability of H before learning of E). (2) says that what it means to say that E is evidence against H is that the conditional probability of H given E is less than the prior probability of H. Intuitively, E is evidence for H if E makes H more likely, and E is evidence against H if E makes H less likely.

A simple example will hopefully help to illustrate these ideas in an intuitive way. Suppose that I roll a fair, six-sided die. Without looking at it, I think about the hypothesis that the die landed on an even number. So, let H = "the die landed on an even number." Since we are assuming this is a fair die, the die is equally likely to land on any particular number. Now, there are three even numbers (2, 4, 6), and six total numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Hence, the prior probability of H, that is, the probability of H given only my background knowledge that a fair, six-sided die was rolled without any further information, is 3 / 6 = 1/ 2. So, we write Pr(H) = 1 / 2.

Now, suppose that a trusted friend of mine informs me that the die in fact landed on a number greater than 3. This information affects the probability of H. So, let E = "the die landed on a number greater than 3." What I now want to know is what the probability of H is given E. That is, I want to know what the probability is that the die landed on an even number given that the die landed on a number greater than 3. To determine this, we can reason as follows: There are three possible numbers greater than 3: 4, 5, and 6. Since it is a fair die, these three numbers are each equally likely. Now, two of them are even, and there are three total. So, the probability that the die has landed on an even number given that it has landed on a number greater than 3 is 2 / 3. So, we write Pr(H | E) = 2 / 3. Thus, E has raised the probability of H and is therefore evidence for H. If instead H were the hypothesis that the die landed on an odd number, then E would lower the probability of H and would therefore be evidence against H.

Before closing this section, a useful fact to note is that Pr(H | E) > Pr(H) just in case Pr(E | H) > Pr(E | ¬H). That is to say, E is evidence for H if and only if E is more probable if H is true than it is if H is false. Generalizing this gives us what is known as the likelihood principle in confirmation theory:

Likelihood Principle: Let H1 and H2 be two competing hypotheses. A piece of evidence E counts as evidence in favor of H1 over H2 if E is more probable given H1 than given H2, i.e., if Pr(E | H1) > Pr(E | H2).

With this understanding in mind, let us proceed to the articles.

Popular Apologetics on Reversing the Problem of Evil

Article 1: Evil as Evidence for God by Greg Koukl

Koukl argues that the problem of evil presupposes the existence of objective evil. As he writes, "The entire objection hinges on the observation that true evil exists 'out there' as an objective feature of the world." Now, the existence of objective evil entails the truth of moral realism and the existence of an objective moral standard. For various reasons (read the full article for all the details), Koukl argues that God is the best explanation for the existence of objective morality: "What is the best explanation for the existence of morality? A personal God whose character provides an absolute standard of goodness is the best answer." For Koukl, moral realism is (strong) evidence for God's existence. Moreover, the existence of objective evil entails moral realism. Koukl's conclusion is that "Surprisingly... evil is actually evidence for God, not against Him." Evidently, then, his overall argument is as follows:

- The existence of objective evil entails moral realism.

- Moral realism is evidence for the existence of God.

- Therefore, the existence of objective evil is evidence for the existence of God.

Article 2: Evil is Evidence God Exists by J. Warner Wallace

Warner follows a very similar line of thought. He asks, rhetorically, "In a universe without God, can true evil exist in the first place?" He goes on to make the bold statement that "while the existence of evil might at first appear to be a strong evidence [sic] against the existence of an all-powerful, all-loving Divine Creator, it may actually be the best possible evidence for the existence of such a Being." Similar to Koukl, Warner argues that God provides the best explanation of moral realism by serving as an objective and transcendent standard of goodness. All in all, Warner's argument is essentially the same as Koukl's.

Article 3: How Evil Proves God's Existence by Pat Flynn

Flynn contends that "evil raises the likelihood of God." Like Koukl and Wallace, Flynn focuses on the necessity of there being an objective moral standard in order for the problem of evil to get off the ground: "To call something evil—that is, really and truly bad (not just a matter of opinion)—we require a moral standard. With no moral standard, nothing can fail to be or do what it should or could have done, and there’s no basis for calling anything evil." And theism, Flynn argues, unlike atheism, clearly provides an objective moral standard. In consideration of the prospects of there being an objective moral standard on atheism, Flynn's writes, "even if it is not impossible, surely, it is fantastically improbable." Moreover, Flynn argues that it is in virtue of this that evil is actually more expected on theism than it is on atheism. Flynn writes:

The problem of evil points toward the existence of God—the God hypothesis, as it were—because if atheism were true, I would not expect there to be any evil at all... precisely because I would not expect there to be a... moral standard... But because there is evil and because theism better predicts or explains those things needed to make sense of evil, then evil provides great evidence for the existence of God.

So, because moral realism is likelier on theism than on atheism and because the existence of objective evil entails moral realism, it apparently follows that evil is therefore evidence for theism. The overall argument therefore seems to be the same as the arguments of Koukl and Wallace.

One notable addition of Flynn's discussion, however, is that he allows that while evil (greatly) raises the probability of the existence of God, the existence of evil might still be highly unlikely given the existence of God. In other words, it might be that even though Pr(God | Evil) is high, it is nevertheless the case that Pr(Evil | God) is low. This is a nice (and correct) insight that allows defenders of the strategy of reversing the problem of evil to still acknowledge the strong intuition that the existence of evil (especially the kinds and quantities of evil that we see all around us) is unlikely given the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good Creator of the universe. The key takeaway, though, is that Flynn's main argument is essentially the same as the arguments of Koukl and Wallace.

Article 4: The Existence of Evil Proves That God Exists by Daniel King

King opens his article by asserting that "While the existence of evil is a serious problem, it is an even more serious problem for atheists because the existence of evil is only further evidence for God’s existence." The reason is by now a very familiar one: given the existence of God, there is an objective moral standard, while given atheism, there is seemingly no objective moral standard. As King writes, "without God, the terms 'good' and 'evil' in the mouth of an atheist are subjective, relative terms, not moral absolutes." Therefore, insofar as there is objective evil, there must be an objective moral standard; consequently, evil is actually evidence for the existence of God.

Article 5: Evil Exists; Therefore, God Exists by Paul Copan

Copan argues along the same lines as each of the foregoing authors, though his presentation is a bit more sophisticated. He lays out the steps of his argument as follows:

- If objective moral values exist, then God (most likely) exists.

- Evil exists.

- Evil is an objective (negative) moral value.

- Therefore, God (most likely) exists.

Copan thinks that the problem of evil presupposes the existence of objective evil and hence—given the above argument—actually serves as an argument for God. He writes, "the problem of evil—the leading anti-theistic argument—turns out to be an argument for God’s existence."

A number of comments are in order. I take it that placing "most likely" in parentheses in (i) and (iv) is meant to indicate that the statements can be read with or without "most likely." If read without "most likely," the statements become entailments: the existence of objective moral values entails that God exists, and the conclusion that God exists is entailed by the premises of the argument. (This version of the argument has been defended by William Lane Craig). Let us refer to this reading as the logical version of the argument. If instead the statements are read with "most likely," the statements become probability statements: the existence of objective moral values makes the existence of God highly probable, and the conclusion that God exists is made highly probable by the premises of the argument. Let us refer to this reading as the evidential version of the argument.

Regarding the evidential version, in order to add some formal precision to the argument, I propose that (i) should be written as a statement of conditional probability: the probability that God exists given that objective moral values exist is high. A similar point applies to (iii): the probability of the conclusion that God exists given the truth of the premises is high. One difficulty here, however, is that probabilities are always relative to general background evidence, which Copan leaves unspecified. A simple way to sidestep this issue is to assume that Copan thinks that (a) the existence of objective moral values is evidence for the existence of God and is such that when added to whatever background evidence Copan has in mind, renders the existence of God highly probable. From here, (iii) immediately implies that the existence of evil entails the existence of objective moral values. In order to get to the conclusion, it seems that Copan must infer from (a) and (iii) that (b) the existence of evil is evidence for the existence of God and is such that when added to whatever background evidence Copan has in mind, renders the existence of God highly probable. Finally, Copan must infer from (b) and (ii) that therefore (iv) the existence of God is highly probable.

Understood in this way, the evidential version of Copan's argument is committed to the soundness of the above formulated argument that I attributed to Koukl, Wallace, Flynn, and King. Consequently, if that argument is not sound, then neither is the present argument. Hence, for the purposes of this post, it suffices to consider that argument and the logical version of Copan's argument.

Assessment of the Arguments

To summarize, we have essentially seen various presentations of following the two arguments:

Argument 1:

- The existence of objective evil entails moral realism.

- Moral realism is evidence for the existence of God.

- Therefore, the existence of objective evil is evidence for the existence of God.

Argument 2:

- If objective moral values exist, then God exists.

- Evil exists.

- Evil is an objective (negative) moral value.

- Therefore, God exists.

Further, we have seen that the defenders of these arguments hold that the problem of evil presupposes moral realism. Beginning with this point, it is not obvious that it is true. Paul Draper, for instance, argues that the atheist can present suffering in purely descriptive, non-moral terms. While such suffering might not be objectively evil given atheism, it would be objectively evil given theism, and for this very reason it is still reasonable to think that suffering would be more expected given atheism than it would be given theism.

In response to this, it could be argued that it is unreasonable to think that suffering would not be objectively evil and that therefore the most plausible version of atheism affirms moral realism. Consequently, atheistic defenders of the argument from evil ought to affirm moral realism. In any case, for present purposes, I will simply grant that the problem of evil presupposes moral realism insofar as it is committed to the existence of objective evil (which I will also grant). Nevertheless, it is important to note that defenders of reversing the problem of evil must ultimately contend with Draper's argument, and the defenders I have surveyed in this post have not done so.

What I now want to show is that Argument 1, as intuitive as the underlying logic might seem, is not even logically valid. That is to say, even if the premises are true, the conclusion does not logically follow from the premises. It is possible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false. I will demonstrate this with a counterexample. To begin, Argument 1 can be semi-formalized as follows:

- Evil → Moral Realism.

- Pr(Theism | Moral Realism) > Pr(Theism).

- Therefore, Pr(Theism | Evil) > Pr(Theism).

The general logical form of the argument is as follows:

- A → B.

- Pr(C | B) > Pr(C).

- Therefore, Pr(C | A) > Pr(C).

The invalidity of the inference from the premises to the conclusion is proved by the following counterexample:

- If something is a zebra, then it is an animal.

- The probability that a randomly chosen object is a cat given that it is an animal is greater than the prior probability that it is a cat.

- Therefore, the probability that a randomly chosen object is a cat given that it is a zebra is greater than the prior probability that it is a cat.

In this counterexample argument, both premises are clearly true and yet the conclusion is clearly false. The first premise is obviously true since all zebras are animals. The second premise is also obviously true. If we remove all non-animals from consideration, then there is a greater chance that the randomly chosen object is a cat. This is similar to the die example given earlier: if we remove all numbers less than 4 from consideration, there is a greater chance that the die landed on an even number. Finally, the conclusion is obviously false. The probability that something is a cat given that it is a zebra is zero, and the prior probability that the randomly chosen object is a cat is greater than zero.

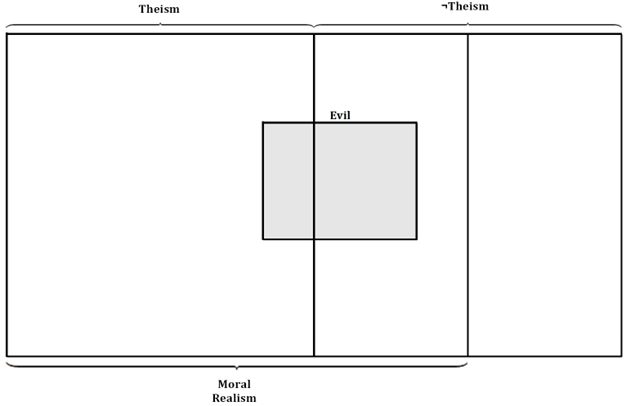

So, the argument that Koukl, Wallace, Flynn, King, and Copan put forward as an attempt to turn the problem of evil on its head by showing that evil is actually evidence for God rather than against God is not even logically valid and therefore fails. The atheist can grant that evil entails moral realism, moral realism is evidence for theism, and yet still maintain that evil is evidence against theism. The diagram below depicts a possible probability space in which this scenario obtains:

In this scenario, if we acquire moral realism as evidence, then the probability space gets updated so that theism occupies a greater proportion than atheism (and thus theism becomes more probable than atheism). However, if we then acquire evil as evidence, the probability space gets updated so that theism occupies a lesser proportion than atheism (and thus theism becomes less probable than atheism). Thus, the problem of evil will retain its force despite the truth of all of Argument 1's premises. Hence, Flynn's statement that Argument 1 "is all that is needed to diffuse the problem of evil—or if it remains a problem, then it is a problem only for atheism" is mistaken.

This brings us to Argument 2, which is the logical version of Copan's argument. In this case, the problem of evil is truly turned on its head, for it can be derived from Argument 2's premises that the existence of (objective) evil entails the existence of God. Hence, assuming that the problem of evil must presuppose the existence of objective evil, it follows that the problem of evil relies on a premise which entails the very thing it is trying to disprove (viz., the existence of God). However, this strategy will only be guaranteed success if the truth of the premises can be proved with complete certainty, and this seems like an unrealistic expectation. Surely, it can be rational for the atheist to have some doubt about the premises.

Consider the first premise: If objective moral values exist, then God exists. This is a strong claim. The claim is not merely that the existence of objective moral values greatly increases the probability that God exists; rather, the claim is that the existence of objective moral values entails that God exists. Given how strong this claim is, we might reasonably be less than certain that it is true. And if we are less than certain about the truth of this premise, then there will be some nonzero (epistemic) probability that objective moral values exist and yet God does not exist. From here, the atheist can argue that the uncertainty in the premise is significant enough that however small the probability for the existence of objective moral values given atheism might be, evil is still more expected in this scenario than it is given theism. Consequently, evil would still be evidence against theism, and evil would still result in making theism less probable than atheism. Now, perhaps the atheist is wrong here. The key point, however, is that Copan and company have not shown that the atheist is wrong.

A Way Forward

I think the best way forward for the theist who wants to defend the strategy of reversing the problem of evil at this point is to argue that the probability that evil exists given theism is greater than the probability that moral realism is true given atheism. In such a case, since the existence of (objective) evil entails the truth of moral realism, the probability that evil exists given atheism is less than or equal to the probability that moral realism is true given atheism. It then follows that the probability that evil exists given theism is greater than the probability that evil exists given atheism. Hence, evil would be evidence for theism in this case. This argument can be semi-formalized as follows:

- Evil → Moral Realism (premise).

- So, Pr(Evil | ¬Theism) ≤ Pr(Moral Realism | ¬Theism) (from 1).

- Pr(Evil | Theism) > Pr(Moral Realism | ¬Theism) (premise).

- So, Pr(Evil | Theism) > Pr(Evil | ¬Theism) (from 2 & 3).

- Therefore, Pr(Theism | Evil) > Pr(Theism) (from 4 and the likelihood principle).

Bayesianism is nonsense

ReplyDeletePr(Bayesianism is nonsense | Anonymous says so) = 1. ;)

ReplyDelete